Maps

The depth and clarity of description contained in early Jesuit books are undoubted reasons for the ongoing popularity of these writings. At the time of their publication - from the time of the foundation of the order in 1540 through to their suppression in 1773 - they were well received because of the information they contained about everything from customs to culture. Now they are important and rare primary source documents that reveal much about not only historical settings but also such things as the growth of the printing industry, the dissemination of knowledge in the early modern world and the rise and fall of spheres of power, among other things.

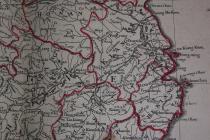

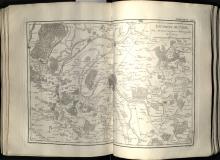

One area where these primary source documents continue to fascinate is in the field of cartography – which reflects the Jesuit interest in exploration. This desire itself emanates from the Jesuit ideal of being men on mission, prepared to go even to the ends of the earth. Consequently, while there are Paris metro stations named after Jesuits so too are there craters on the moon that commemorate the Jesuit spirit of enquiry. Jesuits like Père Jacques Marquette (1637-1675) canoed the northern Mississippi in 1673 and António de Andrade (1580-1634) crossed the Himalayas in 1624. Setting them apart from most other explorers at the time, however, was their scientific training (especially their advanced mathematic knowledge), which enabled them to record and map what they saw. These maps have come down to us today.

In relation to the cross-cultural exchange being highlighted on this website, and concerning the maps in the collection of books held at the Burns Library of Boston College, it is enough to note that some of the pre-eminent cartographers of the day, including Jean Baptiste d’Anville and the Blaue family of Amsterdam, included Jesuit information in their own maps.

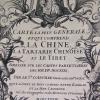

Furthermore, at the behest of the emperor, Jesuits in China mapped the length of the Great Wall(s) in 1708 and then between 1710 and 1718 proceeded to map the whole Chinese kingdom. The maps and atlases of China missionaries such as Matteo Ricci, Guilio Aleni, Adam Schall, Martino Martini and Ferdinand Verbiest have also become famous. Jean-Baptiste Du Halde also incorporated much of the China Jesuits work into his encyclopaedia.