Xu Guangqi

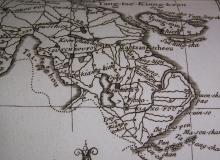

Great attention, and even too much attention, has been paid to the work of European Jesuit missionaries in China. Certainly the manner in which many of them were able to overcome cross-cultural differences and immerse themselves in - what was to them - a new world, was (and is) very impressive. Perhaps even more striking is the fact that much of what these early Jesuit achieved has been sustained even into the present.

This includes, among others, such things as the fact that their translations of European scientific and mathematical knowledge have become part of the scientific history of China, and the manner in which the modern Catholic communities from the north China plains to the south eastern littoral can trace their history back to the arrival of a European Jesuit missionary is worth noting. It is also worth remembering, as Nicolas Standaert and other writers remind us, that the Jesuits were also responsible for introducing Chinese scholarship to Europe at the same time. Standaert consistently argues that, in fact, the Jesuit missionaries were more changed by their Chinese friends than the Chinese communities with whom they engaged were changed by them.

The questions remains, therefore, what brought about this change? Was it Chinese culture at large: this concept of a great ‘Other’, always rising from some Western pre-determined base, still prevalent today? Or, more so, was it rather the individuals with whom the Jesuits met, drank tea and discussed the meanings of life? Given that one of Ricci’s most successful Chinese books was a compendium of classical humanist texts on amity, entitled (rightly enough) On Friendship, perhaps that is the best lens to understand this relationship.

The Jesuits were only able to do what they did in China, because of the Chinese companions, friends, converts and even enemies who engaged with them. Of course the Jesuits' own scholarship and pre-dispositions were important but in fact that only got them a place at the table. Their Chinese companions were critical to the on-going conversation.

Paul Xu Guangqi (1552-1633) was just such a conversation partner, and much more besides. He was the reason the church was founded in Shanghai, he was the collaborator on translation projects with Ricci (including on Euclid’s Elements) and he was a significant protector of the early church. Without Xu, there would have been no Chinese Catholic church, certainly not as it is known today.